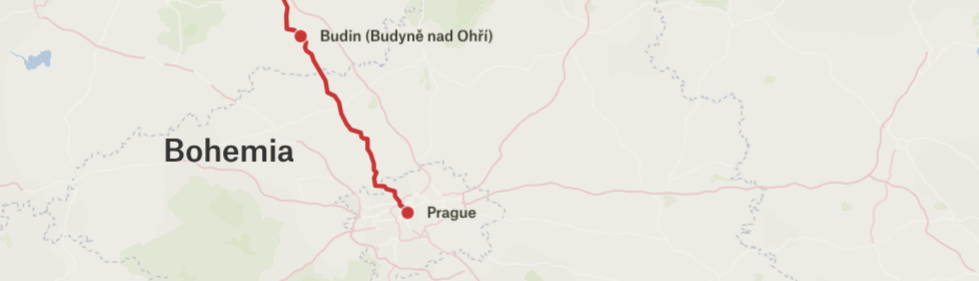

Budin to Prague

"I let the quality of inns trouble me little"

From Budin to here the itinerary marked seven miles,(1) which we marched quite comfortably from half past seven in the morning until half past five in the evening, though we also sat for more than an hour at midday in an inn, where we shared a modest fast-day meal of pancakes and were charged fifty kreuzers for it — a handsome handful of money, I think, for a pancake in Bohemia. It had been cheaper, and better, in Peterswalde.(4) The landlord of The Rose in Budin(2) had a fine house on the outside and a poor one within. The tripe soup, the tough, dry beef, and a leathery roast of goose that might once have saved the Capitol — all were bad; the beds were worse; and worst of all was the price. Everything poor was monstrously dear, as I had been warned beforehand. But, as the saying goes, “Need is a clenched nail.”(5) This innkeeper is the only one in Budin, and, I believe, Küttner(6) has already sung his praises quite sufficiently. For the rest, I let the quality of inns trouble me little: the best is not too good for me, and with the worst I can still make do. It is surely not yet so bad as on an English transport ship,(7) where they pickled us like Swedish herrings; nor in a tent, nor on sentry duty at a fire-post,(8) where I took a stone for a pillow, slept soundly, and let the thunder roll quietly over my head.

In the inn at Budin(2) there was a quodlibet(9) of people telling one another their fortunes, and, it seemed, embellishing them here and there with a few lies. A few Austrian soldiers, grooms, and former artillerymen — all of whom had been prisoners of war in France — together with some Saxons from the contingent,(10) made a worthy group and entertained the rest at length with accounts of their sufferings. One of the soldiers in particular gave such a ghastly description of the lice in the field and in captivity that we others might almost have caught the phthiriasis(11) from his words alone. To me it was merely a comical reminder of my first sea voyage to America,(12) when the English kept us miserably “clean,” and when, from the captain down to the drummer boy, we had such a host of those little creatures that they threatened to gnaw through the rigging.

A wagoner then told, wildly enough, how he and his comrades in Iglau(13) had recently given a few soldiers a terrible beating in a quarrel over some girls. “Where there is a quarrel, there is always a lady in the case,” I thought(14) — a rule that seems to hold even for the Austrian baggage train. One of the soldiers remarked that the wagoners had done something very improper, to lay hands on the defenders of the fatherland; the affair would likely have ended badly for them. “Oh nonsense,” said the wagoner, “they were only legionnaires.”(15) “Ah, that’s another matter,” the soldier replied, appeased; “those are only students and merchant lads who cry for their bread-and-butter after the third march, like the penny whores;”(16) “they can well do with a sound thrashing to cure their ticklishness.”

In Prague we were properly entered in the register by a sort of gate-clerk, who gave us lodging-tickets and sent our passports to the police directorate for endorsement. The gentlemen of the police were, contrary to the habit of their class in other lands, politeness itself; the next morning everything was done within ten minutes, and we had our papers made out all the way to Vienna.(17) Our acquaintances were much astonished at our good fortune, for only recently even travellers with diplomatic passports had met with great difficulties.